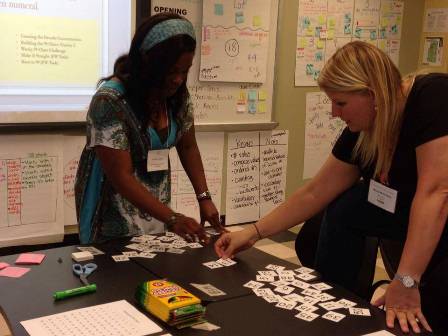

In the

third-floor classrooms of Tucker High School last week, as summer heated

asphalt outside, Georgia math teachers were huddling in circles sharing

strategies, or perching on chairs to sketch out graphs, or gathering, by hand, the

statistics associated with dolphin-therapy patients.

As the job

market changes and the reach of technology spreads, it is as important as it has

ever been for students to leave their schooling with a strong understanding of

mathematical concepts. Rigorous math and science standards are increasingly seen

as key components of global competitiveness.

That means

students – even those who struggle with math, for whom it does not come

naturally – need math, and need the logic skills and critical thinking it

sharpens.

In those

rooms at Tucker High School, teachers took up that task. It was the first of

seven Mathematics Summer

Academies offered by the Georgia Department of Education, all featuring

sessions led by Georgia educators.

“Guided by

teacher feedback and supporting research findings, the 2014 Mathematics Summer

Academy Program will offer the same series of interactive grade level/high

school course sessions at each site,” said Sandi Woodall, director of GaDOE’s

mathematics program. “Each session is focused on the enhancement of content

understanding for the particular grade level or high school course that the

participant teaches. A cadre of Georgia’s master educators crafted the content

for the fifteen 12-hour courses and will deliver the professional learning experience

to peers within this summer’s academy program.”

At the Tucker

workshop, Coordinate Algebra teachers collected their own personal data –

birthday month, miles traveled to reach the high school – on sheets of white

paper taped to the walls, then experimented with ways students could learn to

display and examine similar data.

Analytic

Geometry teachers carefully folded tissue-thin paper into parabolas, talking as

they worked about interactive learning and how to show a concept so that it

provokes real understanding, rather than simply talking about it. They

practiced grading formative assessments. They discussed ways to challenge

students to go further, rather than experiencing the mental shut-down that

difficult subjects sometimes provoke.

Kindergarten

teachers worked on their questioning strategies, practicing on each other – one

teacher in a pair taking the place of a kindergarten student, displaying their

pitch-perfect understanding of how a five-year-old would react, what they would

say, and what tone they would say it in. They worked on using questions to

narrow down that five-year-old understanding, to grasp what the student really

knew and fill in the gaps.

Teachers

across content areas explored curriculum resources. They discussed ways to personalize

learning and address the needs of the struggling student, the on-target student

and the accelerated student alike. They spent time unpacking common

mathematical misperceptions (if there is a 50 percent chance of rain on

Wednesday and a 50 percent chance on Thursday, for example, the probability of

it raining both days is not 50 percent).

In every room

was an effort to get beyond “pure math” and reach “contextual math” – math that

students can understand because they can see it in context.

“They love

that context,” instructor Adrian Throop told a room full of teachers. “They

don’t know that they love statistics.”

For some

adults, math is a blur – something struggled with in childhood and glazed past

in adult life – but, when genuinely understood, it can open up countless doors.

The math

instruction taking place in Georgia is the exact opposite of throwing out

information and hoping it hits. Teachers are putting in the hours necessary to

teach kids math that they can experience – math they can understand.

And, as they

do, those doors will swing open for students.